...and she always knows her place Interview Series

…and she always knows her place is a project promoting female and female identifying driven narratives, exploring what it is to be a woman in contemporary life.

Last year I sat down with Melbourne based Artist, Writer and RRR DJ Eva Lubulwa. We spoke about her multiple creative projects which spawned from a tumultuous time in her life. She experienced the worst racism of her life, a marriage breakdown, and a breakdown of the self. She has used art to build herself up again, into what she says is a ‘truer version of herself.’

Get comfy, this is a great conversation about life as a woman, race, identity, a Trans-Siberian adventure turned nightmare, and finding your way out of a catastrophe of the self.

A: What kind of things are important to you in your life right now?

E: In my life right now, is work. That sounds really weird to say. But I do a lot of creative work at the moment, different projects just give me life. I've been doing a lot of painting, getting into illustration, doing a few art shows and stuff like that. I’m doing my last training session for a radio show and doing my first radio show on Wednesday.

That’s what I do. That’s all I do. When I got back it was a way of processing everything that had happened to me, because I had a lot to process. And then, it’s just kind of snowballed. It’s that anchor at the moment in everything I do. I would say originally I'm a writer. I've written a book, you’re going to think I'm crazy. I’m not crazy. But, I've written a book, which I'm too afraid to publish.

So, I got married to a guy who was afraid of flying. He wanted to live in Europe, so we went from here to Europe without flying. We took two boats, and trains and the Trans-Siberian and the Euro-Rail and ferry's and buses. Along the way I experienced the worst racism I’ve ever experienced in my whole entire life. I crashed as a human being and my identity was levelled, to say the least. Being in a mixed race marriage, he’s Serbian, there were moments where he chose to not partake in the situation as much as he should have. So amongst other things, that had pressure on our relationship. Our marriage broke down, and really for me, it was the race thing that had me going, ‘Like I can’t.’ I needed more and he didn't give it to me. And that’s not his fault because you can’t, I mean we were in the middle of Russia and I was the only black person. Like, you can never actually know what you’re going to do in that situation. Intellectually, yeah, and he’s an intellectual person and he’s a very kind person, when he wants to be. I was with him for five and a half years, he wasn't an arsehole. The book is all about my journey. I wrote it as I was going. It just kind of lays out the journey from where I started here, where I was very racially oblivious. I was like, ‘uhhh yeah I’m Australian’, and people were like 'where are you from?’ And I'm like, ‘Australia.’ And they’re like, ‘yeah but where are you really from?’ And I’m like ‘Australia.’ And I’m getting all riled up about that, and just realising that in different parts of the world all they see is black. So for me, I got to one point on the trip that I apologised for being black.

“just realising that in different parts of the world all they see is black. So for me, I got to one point on the trip that I apologised for being black.”

Because you go crazy. It was eight months of being pointed at, laughed at, stared at, not served, shrieked at. It was constant. People taking photos of you, just coming and snapping in your face, hiding, and somewhere along the line, you go, ‘well I’m the only one who everyone else thinks is crazy. So maybe I’m the one who’s crazy?’

Our trip was just different, you know? Like instead of going down and seeing all the train stations in St. Petersburg. I was in the room crying, with my arms out, afraid to leave the hotel. So it’s different from what you would think, because as soon as I say something like, ‘oh yeah we went to Europe by boat and train.’ Everyone’s like ‘Oh my god! That must be such a great adventure’! I’m like ‘No. It’s the worst thing that ever happened in my life.’ And the best thing. Because I think when you get levelled, what gets built up afterwards is almost a truer version of yourself than what was before. I just wish that I didn't have to get levelled.

So that’s the book. I wrote everything down, and I edited it and edited it down again and refined it. It was just everything it was my whole life on paper, and when I realized that my biggest qualm or my biggest battle was with my race, then I pulled out all the stuff that was about, I don’t know, about my shoes. Some shit, I don’t know. It’s one of those very open books, and I don't really care about my stuff. A lot of the stuff I still struggle with. Like, I battled with mental illness and an eating disorder. I'm not really worried about that stuff. But writing about a marriage breaking down and about his family. That’s kind of like, ‘Oohhh I don't know if I'm ready to pull that out.’ But it’s a story that needs to be told, because I don't think the world realises how racially backwards we are.

A: No. I'm shocked that you had that experience. I thought Europe was more progressive?

E: Yeah, and I mean some places in Europe. Your Scandinavian countries are good. But the eastern European block, Russia and Asia. No. If you're a person of colour it’s very difficult. It’s also about women trying to find themselves, and we all go through this kind of identity journey.

A: Yeah, I kind of feel like that what this project is about. So I guess it’s broadly ‘what it’s like to be a women in the world at the moment?’ Particularly with all the political things that have been going on all over the world, obviously in the US…..One push back I hear often is ‘oh yeah, but you have it pretty good you know?’

E: That is the most demeaning term that ever. Yeah, I fight a lot against that, because it’s like, 'settle for not so bad.’

A: Yes! Exactly.

E: And it’s like, ‘well I'm going to aim for perfect. And maybe one day we’ll reach that, and maybe one day we won’t. But at least we’ll get further and further along. Don't ask me to settle for; well it’s not as bad as over there.’

‘You don't live in a third world country, at least you have voting rights, and women can pretty much do everything.’ And it’s like, ‘well can they? Really?’

A: Yeah exactly. Can I walk home at night alone?

E: For real, no!

I was talking to people in Brussels when I was coming back, they were like, ‘oh so you're going back to Australia! Oh that’s going to be cool, you can go out!’ I’m like, ‘yeah, Australia’s a little bit stabby and rapey.’ You know? And the one thing that Australia needs to know is that it’s very prominent here. I could walk home in Brussels. I would walk around at three o’clock in the morning, you’d see someone and it’d be ‘bonjour, bonjour, au revoir’ and then you’d walk off. There was no moment where I thought someone’s going to get me in the bushes. Whereas I don't even like doing exercise in the morning because while we were over there, there was like three or four different cases in a short period of time where men had assaulted women like in Brunswick or Parkville, or something like that. I was like ‘Oh Australia, Oh Melbourne even.’

A: Yeah. Its a real undercurrent in our society, is violence against women. It’s reflected in our language, and attitudes.

E: And it’s like don't be uptight. Protect yourself more. You know, that whole victim shaming.

A: Didn’t the Police Commissioner say (at that time) women should have an escort home from work? Like, it’s 6pm! That’s the solution?

E: Oh, there was a big protest up on Sydney Road going like what are you guys doing? You're not talking to the perpetrators and going; ‘do you know what, you're really fucked up! You need to put that shit together and stop getting handsy with people who don't want you.’ Instead you're telling girls to zip up to here, and walk safely at night. But then in the same breath, Muslim women; too much! You're telling us that we’re sluts and to cover up, then you're telling them their too covered and they should have their freedom by bringing their boobs out. Like you guys gotta decide, you’re confused!

“I had to mourn the fact that, that path for me, is dead.... my path is not going to look like what I’ve been taught my path is going to look like.”

A: Yeah. It’s really hard it talk about it in a way that is respected and not just ‘whinging.’ Because again, everything you do is a political statement.

E: Oh honey, try being a black woman.

It’s like; ‘you guys are so angry!’ Nah, we talk in a different level, a different level of passion. I’m not necessarily angry, but like even if if I was, I got shit to be angry about.

A: Yeah, that’s it. Don't we have a reason to be angry? Shouldn’t we be angry?

E: Yeah, I know. Why don't you guys fall in line and I’ll be nicer to you. (Lol) Do you know what I mean? and it’s stupid because we live in this progressive world and we still have these traditions l values.

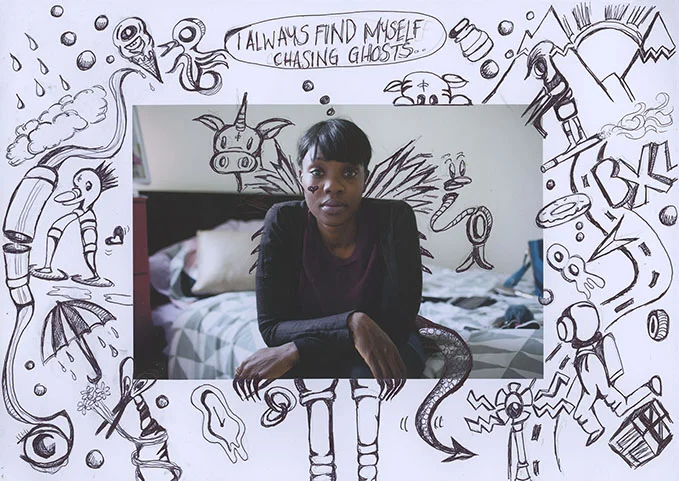

For seven years I just drank everyday. From the time I started uni, to the time I was 25. I was drinking everyday. I graduated, I don't know how? But I could never keep down a job, because I was drunk most of the time. I gave up drinking when I was 25, and I was playing catch up, and my idea of catch up was the traditional pathway, you know? I just had to get a boyfriend who would stick around for long enough, and then he would marry me and then we’d have a dog, then three children, then I would be okay. My friends were already a fair bit in front of me. I got that nine to five job that paid me X amount and that increased and then I would be able to get a house loan. And then I got married to a crazy person who wanted to go overseas by boat. Which totally desecrated the whole idea of having children, because we were broke. When I came back, I realised that I probably didn't want to have children right now. Because you cant do this shit. Like, there is a level of craziness that goes along with this (creative work). Like my bed, just pen marks, because I draw in bed, and I stick it up on the wall. It’s crazy, it’s an obsession. You can’t say to a little baby, ‘can’t you just wait for five hours? Mama’s going to be back, the fridge is open; there you sort yourself out.’ So I was like ‘okay, let it go.’ And I had this mourning that happened because everyone was on their second child. It goes like this ‘oh my god, oh my god I'm pregnant! Oh my god I'm pregnant!’ and all with a cute Facebook update, a picture of the ultrasound or something, and I had to mourn the fact that, that path for me, is dead. And it’s not that I can’t have the baby, maybe I’ll traditionally go down that path of meeting someone again. But my path is not going to look like what I've been taught my path is going to look like.

Even sometimes the most progressive women still tie into those old traditional values of what a woman should be. I go through these things like ‘I need to get a boyfriend because who am in the world if I don't have a man? Who am I?’

A: Yeah I go through the same struggles. The role model for all women seems to be that traditional mother/wife. And when you're not that …I don't even know what my life will be like in the next ten years. I’ve got no real examples out there I could try to model my life on.

E: You're like 'who do I clutch to?’ I mean I've got Oprah and Shonda Rhymes. I mean Oprah’s a little obsessed with her dogs, but whateves. It’s that thing, it’s scary. But the other scary thing is, for mothers and I feel sad for them as much as I’m like, ‘oh why can’t I just be like the rest of my friends?’ I feel sorry for them because there is an extra pressure that has come from being in a progressive world. You aren’t just a mother who stays at home and the grandparents help, and you raise a kid, and its beautiful. You now have to go back and study and work part time and feed your kids organic and have a competition with whose progressing more in their development. All of that crap is added onto the fact that your raising something that wont let you sleep. Literally. To have to wake up and feed someone and care and not shake it because that’s illegal. I feel really sorry for Australian and sometimes a lot of western Mum’s because they're being asked to do it all. Without the support. We live in a very isolated society, so it’s not like they’ve got heaps of people coming in and going, ‘oh I cooked you this.’ We don't live in that world. So they're asked to do all of that stuff and they don't have the support and then they're looked down on if they get help. ‘Oh my god don't send you're child to day care.. really your going back to work full time?’ So as much as I’m like ‘shut up about your kids,’ I also feel sorry for them.

A: They have there own struggles. Well, everyone does.

E: Yeah yeah yeah. Especially when I find that kids put your life on hold for a certain period of time. And I feel like as soon as you get your sanity back you have the urge to have another one.

Art is full time work and it’s finding people, it’s talking to people, and it’s also finding a change. I think that sometimes people think that the only way women can make a change is to give birth to a male that will make a change. It’s like, ‘no. If you want equal opportunity, let me slay. Let me do it, because I can.’ I can be the person that talks about race issues, I can be the person who talks about making a change in this world for women, for black people, for men. Fuck it, I can do that. If Tony Abbott can talk about women, and women’s rights, I can frickin talk for men too.

A: Your art is about identity?

E: Yes. What happened is when I got back, this girl asked me to do a show. I started drawing and what came up was the fact that I was really blind to my heritage, and because I was blind to my heritage I got into that stupid situation where I apologised for being black. So it became this process of re-defining who I was, and looking at it through African prints, through just what it meant. It kind of came organically. It became this story about the journey.

One of the things that I have always been connected to in the African community, you can never get away from, is hair. African hair is a fucking nightmare. The plaiting and that ritual that you go through. When you go somewhere and you sit there for 14 hours and someone plaits your hair. And all the different hair styles you go through as you’re growing up. You remember when Monica was wearing a weave and Brandy was wearing braids, and you wanted to be like Brandy so you definitely had to wear braids. But then you got older and Brandy stopped wearing braids, and so Monica and Brandy were both wearing weaves. So then this connection that you have to everyone who is kind of, my African peers I guess, have had similar hairstyles. Similar things where you go to your parents,‘what were you thinking? My hair was standing on end!’ There was a whole room that was an ode to the hairstyles… and so yeah it was all about being blind to my heritage. But the other aspect to it is they all have this freaky kinda weird things going on, whether its scales or tails. The whole statement is that if your are blind to your heritage you become a freak. Because everyone else can see it. Everyone else can see the patterns, everyone else can see the uncomfortable. You’re walking through the world thinking you’re okay, but everyone is judging you on totally different aspects from which you are judging yourself.

“sometimes people think that the only way women can make a change is to give birth to a male that will make a change. It’s like, no. If you want equal opportunity, let me slay. Let me do it, because I can.”

After that I got home and life was Tinderised. There’s a whole series that is on technology and this dance that we do with technology. I really want to do a radio show called Love Songs and Devastations. Which is just based on people sending in their Tinder stories. I'm not on Tinder, I'm in Tinder recovery. It’s been two weeks since my last swipe. Before I got home I was like, ‘I want to date, I want have a job.’ I had to find my own apartment overseas. I got it all online, I had to find a car overseas. I was always on job websites, I was always on Facebook, I was always on Tinder, Snapchat because I needed to get back in contact with people, WhatsApp. Like my Mum text messages on 5 different applications! I can never find the shit you know, which one? And that was my life. I realised that my identity is influenced a lot now by not only Australia, and what’s going on here, but what’s going on on Instagram, which is very American. I gleam from all these places. I kind of write about it in my book because I'm African Australian, born here and bred here, and that is different from African American. But sometimes; and it’s like what you were saying with, ‘I don't have kids, I don't see someone doing it, who do I follow?’ You start digging at, like just kind of grasping for stuff. A lot of my identification comes from there, and now has expanded to a lot of other African communities and stuff like that. But I'm getting this stuff from the internet, you know? This isn’t a one on one physical contact thing, this is like ‘Ohhh yeah that picture, I get that. Oh that thing, maybe I’ll try that. Maybe I’ll do that because that’s the culture, that’s the box that I think that I fit into.’ But that box is created with one’s and zero’s. So, it’s weird. It’s interesting because I’ve had to define myself. If your talking about definition of self as a woman you’ve walked into a like fricken crater of I’m still doing it.

Art for me is something that I was in a lot of trauma when I came back and I hadn't fully processed all the race stuff or the divorce stuff, or relocation. Brussels, where I was living, I’d be standing at the bus stop and I’d look around and there would be seven other black people. On minimum. I know that because I started counting when I knew I was coming back here. Australia’s a very white world. A very, very white world. I went to dinner with a friend on Thursday, and we were sitting there talking about this race stuff and I looked at her in the eyes and I said, ‘do you know that there is only two other black people in this whole entire restaurant and one of them is in the kitchen?’ She was like ‘no,’ and I was like, ‘I do.’ She was talking about not seeing colour. Which is the fucking dumbest sentence. She was like, ‘what do you want me to do? How do you want me to help you?’ Because she’s actually a really really really nice chick, and she really gets affected by racism, and her way of saying 'I'm not racist and I don't understand it,’ is ‘I don't see colour.’ I was like, ‘start seeing colour. Because what you’re saying is that you've turned off that switch. But it’s not a switch that I get to turn off, this is how I walk through the world. I know that the only one of me is in the kitchen. I'm like yep so I'm not the only one in the whole place.’ We were at the Cornish Arms, the place is huge, and it’s something that I notice. It’s something that I always notice even when I don’t. It’s not a conscious thing that happens, it is something where I'm like, ‘Oh, we did that again, okay.’ So what I was trying to say is, for me art is a way of understanding stuff that you can’t put words to. Because sometimes all you can do is put pictures or symbols or something towards it. Even now writing about this stuff; I wouldn't even know where to start, because I'm still on the journey.